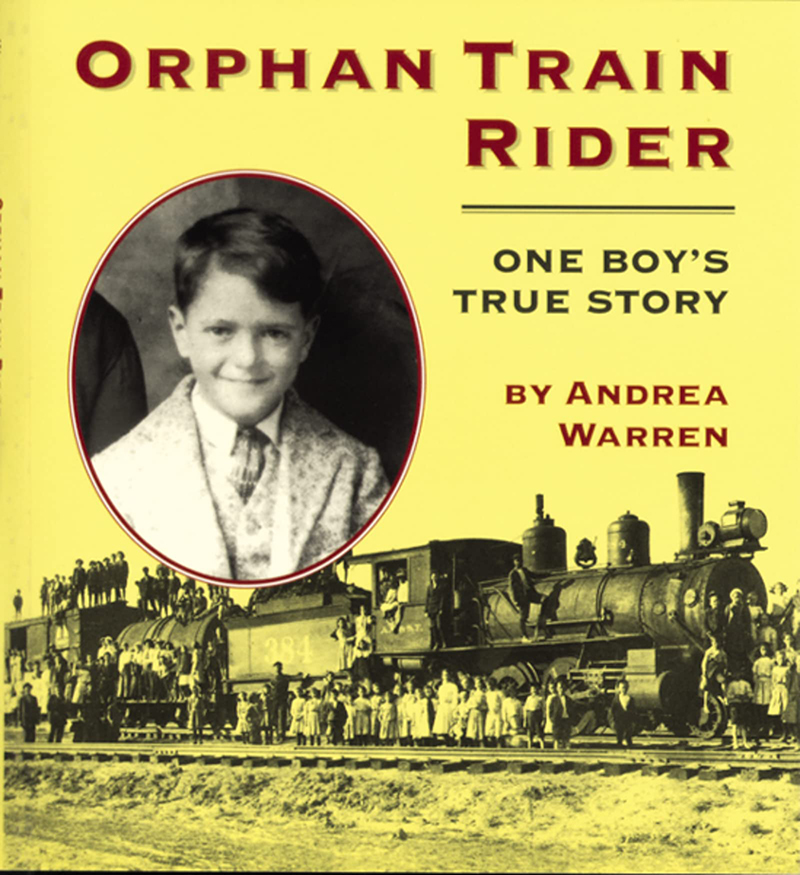

Orphan Train Rider: One Boy’s True Story

by Andrea Warren

Publisher: Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston.

Andrea Warren taught high school history and English, wrote for a newspaper, and edited a magazine before becoming a full-time writer.

Using one young man’s journey as her focus, Warren tells the amazing, sometimes heart-warming, and often tragic westward journey that more than 200,000 children took on the Orphan Train between 1854 and 1930 in search of families. Although he was not technically an orphan, Lee Nailling’s father placed him and his brothers in an orphanage after their mother’s death. Dressed in new clothes, Lee rode the train from Upstate New York to Texas in 1926 with two of his six siblings. Not all children found homes, and many were taken in by families who abused them or used them as workers. Lee was lucky to have been placed with loving and understanding parents who renamed him and raised him as their own; he was luckier still to be reunited with some of his siblings later in his life.

It is thought that as many as 250,000 children rode orphan trains. This “placing out” program was the forerunner to modern day foster homes. Some say they were a good thing; others are horrified at the thought of lining children up to be looked over by prospective parents.

It’s estimated that perhaps 50 percent of the children found good homes. The other 50 percent were taken as workers or were shuffled from home to home or abused in various ways. Yet even these orphan train riders, frequently express their gratitude to the orphan trains for giving them a chance at life–a chance often denied them in the brutal environments of a city that offered no shelter.

The children became homeless for a variety of reasons. Many were the offspring of newly arrived immigrants who fell on hard times and could not support their families. Some were removed from their homes for abuse. Others ran away. Sometimes children were orphaned when their parents died of illness or from accidents.

The orphan trains were started by a minister named Charles Loring Brace. He worked in New York city’s slums and was worried about homeless children. In 1853, Brace began the Children’s Aid Society, which started the orphan trains to find families for these destitute youngsters. The notion was that farm families could use the children’s help, and in return would feed and clothe them, and in every way treat them as members of their families. When it worked this way, as it often did, it was a satisfactory solution all around.

Most children described the selection process at the end of the train ride as traumatic. They wanted badly to make a good impression and be chosen, yet it was so difficult to be stared at, checked over, and sometimes rejected.

For those who currently work with foster homes or adoptions, this book sheds light on the need we still have and how it was met over a century ago. The book is a simple read but insightful into the social movement that predated foster homes, adoption agencies and homeless shelter.